Iron Deficiency Symptoms in Trees: What to Look For

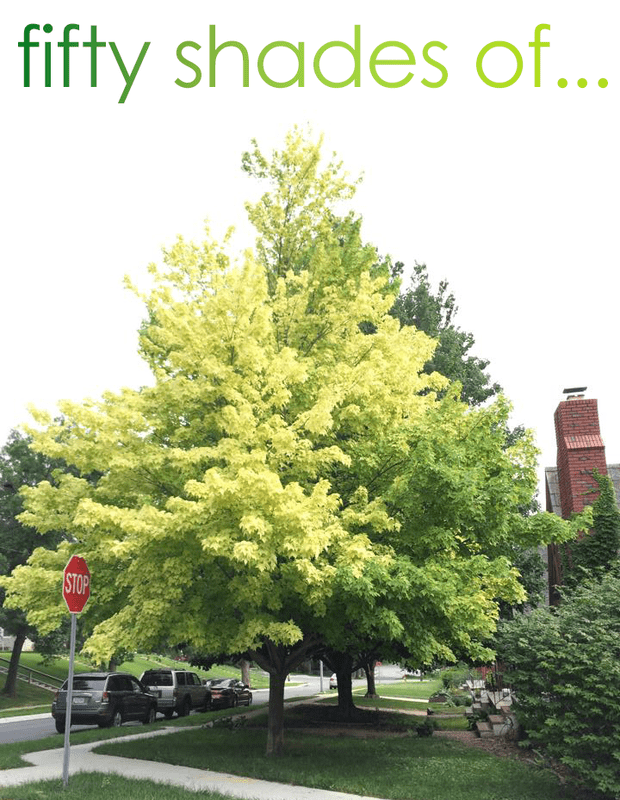

In early to mid-summer, symptoms of iron deficiency often appear as leaves turning yellow or light green. This discoloration may affect the entire tree or only sections of the canopy. When you look closely at affected leaves, you’ll notice distinct green veins against the lighter leaf tissue. As iron deficiency progresses, leaves may scorch, turn brown, fall prematurely, and eventually lead to limb dieback.

Why Alkaline Nebraska Soil Causes Iron Deficiency

Nebraska soils are generally alkaline, with a pH above 7. While these soils contain ample iron and manganese, high alkalinity makes these nutrients insoluble and unavailable to trees, which directly contributes to iron deficiency (Chlorosis). Simply adding iron to the soil may not correct the problem. Iron deficiency symptoms are often more severe when trees are also dealing with compacted soil, poor drainage, and low oxygen levels.

According to the University of Nebraska Extension Program, “Eastern Nebraska tends to have high soil pH, also known as alkaline soil, which can cause problems for some plants, like river birch, pin oak, big-leaf hydrangeas and blueberries to name a few. Alkaline soil changes the availability of certain plant nutrients, often making them less available, resulting in deficiency symptoms.

To learn more, the University of Nebraska Extension has a helpful overview of iron chlorosis, symptoms, and contributing soil conditions: https://lancaster.unl.edu/managing-chlorosis-trees/

Can Iron Chlorosis Kill a Tree?

Yes—iron deficiency can kill trees, especially when it persists for multiple growing seasons without effective correction. Iron is essential for chlorophyll production, and chlorophyll is what allows trees to convert sunlight into usable energy through photosynthesis. When a tree can’t produce enough chlorophyll, its leaves lose their green color (chlorosis), and the tree’s overall growth and energy reserves begin to decline.

As iron deficiency becomes more severe, trees may show stunted growth, poor vigor, and increasing canopy thinning. Over time, leaves can scorch along the margins, turn brown, drop early, and lead to branch dieback—sometimes progressing to decline that is difficult or impossible to reverse in mature trees.

A tree weakened by iron deficiency is also more vulnerable to secondary issues. Reduced vigor limits a tree’s ability to defend itself and recover from stress, making it more susceptible to insect infestations, disease pressure, and environmental injury.

How to Manage Iron Deficiency in Trees (What Works—and What Doesn’t)

There are several approaches to managing iron deficiency, though some are more effective than others. Because iron chlorosis in Nebraska is often tied to alkaline soils (high pH) and reduced iron availability—not a lack of iron in the soil—treatments should focus on improving growing conditions and correcting uptake limitations.

- Water during dry periods, but avoid overwatering.

Drought stress can worsen tree decline, but saturated soil reduces oxygen in the root zone. When roots don’t receive enough oxygen, they can’t function properly, and iron uptake becomes even more limited. Overwatered or compacted soils can therefore intensify iron deficiency symptoms. - Mulch properly to improve soil conditions.

A thin layer of mulch can help stabilize soil moisture and temperature and improve overall root-zone conditions. Keep mulch shallow and away from the trunk to reduce the risk of excess moisture and trunk decay. (Avoid plastic sheeting or barriers that restrict oxygen movement into the soil.) - Avoid fertilizing with high nitrogen or phosphorus near affected trees.

High phosphorus levels can make iron chlorosis worse, even when iron is present in the soil. This is why “more fertilizer” is often the wrong move when trees are already showing yellowing from iron availability issues. - Be cautious with soil amendments—they often underperform on established trees.

In high pH soils, iron is frequently “tied up” and unavailable. Even if you add iron, results may be inconsistent unless the treatment meaningfully improves availability or delivery to the tree. This is especially true in challenging Nebraska soils where pH and site conditions remain unchanged. - Choose species that tolerate alkaline soils for long-term prevention.

There are several approaches to managing iron deficiency, though some are more effective than others. Because iron chlorosis in Nebraska is often tied to alkaline soils (high pH) and reduced iron availability—not a lack of iron in the soil—treatments should focus on improving growing conditions and correcting uptake limitations.

- DO- Water during dry periods, but avoid overwatering.

Drought stress can worsen tree decline, but saturated soil reduces oxygen in the root zone. When roots don’t receive enough oxygen, they can’t function properly, and iron uptake becomes even more limited. Overwatered or compacted soils can therefore intensify iron deficiency symptoms. - DO- Be cautious with soil amendments—they often underperform on established trees.

In high pH soils, iron is frequently “tied up” and unavailable. Even if you add iron, results may be inconsistent unless the treatment meaningfully improves availability or delivery to the tree. This is especially true in challenging Nebraska soils where pH and site conditions remain unchanged. - DO-Choose species that tolerate alkaline soils for long-term prevention.

Some trees are simply more prone to chlorosis in high pH environments, so selecting tolerant species is often the most cost-effective, long-term solution when planting new trees. - DON’T- Mulch properly to improve soil conditions.

A thin layer of mulch can help stabilize soil moisture and temperature and improve overall root-zone conditions. Keep mulch shallow and away from the trunk to reduce the risk of excess moisture and trunk decay. (Avoid plastic sheeting or barriers that restrict oxygen movement into the soil.) - DON’T- Avoid fertilizing with high nitrogen or phosphorus near affected trees.

High phosphorus levels can make iron chlorosis worse, even when iron is present in the soil. This is why “more fertilizer” is often the wrong move when trees are already showing yellowing from iron availability issues.

- DO- Water during dry periods, but avoid overwatering.

Iron Chlorosis Treatment: Macro-Injections That Deliver Results

Arbor Aesthetics addresses iron deficiency using a macro-injection system that delivers iron (and manganese, when appropriate) directly into the tree’s vascular system at the root flare. By applying the treatment internally, the tree can absorb and distribute these micronutrients more efficiently than many soil-applied products—especially in alkaline soils around Omaha where iron may be present but unavailable for uptake.

These treatments are performed in the fall, which is an ideal window because trees are still actively moving nutrients into storage while stress from summer heat and drought begins to ease. This timing helps support stronger spring leaf-out and improved canopy color the following growing season. In most cases, clients see noticeably greener foliage, improved vigor, and better overall tree performance as the tree regains its ability to produce chlorophyll and sustain normal growth.

When applied correctly, macro-injections can provide up to three years of benefit, making them a cost-effective option for valuable landscape trees that repeatedly struggle with chlorosis. They are especially helpful for trees with chronic iron deficiency symptoms, trees growing in high pH soils, and trees where long-term improvement is the goal rather than short-term cosmetic change.